‘Getting off the beaten track’ is an often overused phrase, but it’s entirely apt if you’re hoping to explore the less-visited towns and cities across Portugal. Sometimes your destination is the goal; occasionally it’s a bonus, as it can be more about the journey itself and the evolving landscapes the carriage windows frame so perfectly. With this in mind, we give you our pick of Portugal’s Best Railway Journeys…

The Linha do Norte is the granddaddy of the Portuguese rail network.

The Linha do Norte is the granddaddy of the Portuguese rail network.

Lisbon and the northern industrial centre of Porto were the first Portuguese cities to be connected by rail. Inaugurated on 28th October 1856, the initial 40km of the Linha do Norte ran from Lisbon to the small town of Carregado – rather than heading directly north, a more easterly route was chosen to take advantage of the naturally-flat terrain of the Estuario do Tejo.

The start point for Portugal’s oldest line is also the country’s oldest railway station: Santa Apolonia. Its stately facade has been a prominent landmark on the Lisbon’s waterfront since 1865 – the station was inexplicably painted sky blue in the 1990s; thankfully, its original, distinctive red colour scheme made a welcome return in 2022, during work to convert the south wing into the Editory Riverside Hotel.

The start point for Portugal’s oldest line is also the country’s oldest railway station: Santa Apolonia. Its stately facade has been a prominent landmark on the Lisbon’s waterfront since 1865 – the station was inexplicably painted sky blue in the 1990s; thankfully, its original, distinctive red colour scheme made a welcome return in 2022, during work to convert the south wing into the Editory Riverside Hotel.

The line reached Santarem by 1861 and Entroncamento a year later. Entroncamento was, and still is, a crucial hub – if you’re travelling around the network today, you’ll often change trains here. It’s the point at which many of the smaller regional lines intersect with the main line; indeed, the word itself, entroncamento, translates into English as junction. It’s a fitting location for the Museu Nacional Ferroviar – the National Railway Museum, which opened its doors in 2007.

The line reached Santarem by 1861 and Entroncamento a year later. Entroncamento was, and still is, a crucial hub – if you’re travelling around the network today, you’ll often change trains here. It’s the point at which many of the smaller regional lines intersect with the main line; indeed, the word itself, entroncamento, translates into English as junction. It’s a fitting location for the Museu Nacional Ferroviar – the National Railway Museum, which opened its doors in 2007.

The museum charts the one-hundred-and-sixty-year history of the railway network, and its evolution and impact on Portuguese society. It also preserves and exhibits historic locomotives, rolling stock and heritage real estate, including Dom Luis’ royal train, a roundhouse turntable from 1911, and the original workshops which once maintained the country’s steam locomotives.

Approaching the end of 1862, the planning and implementation of the line thus far had been marred in controversy. Following their own domestic railway booms, speculating British and French industrialists promised large investments which failed to materialise, leaving the Portuguese state to pick up the bill. In an effort to reduce costs, the contentious decision was made to bypass the historic city of Tomar.

Approaching the end of 1862, the planning and implementation of the line thus far had been marred in controversy. Following their own domestic railway booms, speculating British and French industrialists promised large investments which failed to materialise, leaving the Portuguese state to pick up the bill. In an effort to reduce costs, the contentious decision was made to bypass the historic city of Tomar.

To the modern-day visitor, Tomar is a peaceful rural town with beautifully preserved medieval architecture – however, at the tail end of the 1800s, the Portuguese monarchy were still acutely they owed their existence to Tomar and its founding father, the 12th century crusader named Gauldim Pais.

Pias was the Grand Master of the Portuguese order of the Knights Templar – his crusading nobles fought for Dom Afonso I, helping to install him as ruler of the Kingdom of Portugal in 1143. As thanks, they were granted estates in key strategic locations across the country, including Tomar where they established their main stronghold. Following the Catholic Church’s violent dissolution of the Templars, the crusaders ‘rebranded’ as the Order of Christ. They swore allegiance to the monarch and were key to Portugal’s Age of Discoveries, helping to establish colonies in Africa, India and Brazil. The Portuguese crown accumulated great wealth, and the Order of Christ was seen as the monarch’s right-hand by generations of kings and queens – and by association, the town of Tomar was an important royal seat.

Pias was the Grand Master of the Portuguese order of the Knights Templar – his crusading nobles fought for Dom Afonso I, helping to install him as ruler of the Kingdom of Portugal in 1143. As thanks, they were granted estates in key strategic locations across the country, including Tomar where they established their main stronghold. Following the Catholic Church’s violent dissolution of the Templars, the crusaders ‘rebranded’ as the Order of Christ. They swore allegiance to the monarch and were key to Portugal’s Age of Discoveries, helping to establish colonies in Africa, India and Brazil. The Portuguese crown accumulated great wealth, and the Order of Christ was seen as the monarch’s right-hand by generations of kings and queens – and by association, the town of Tomar was an important royal seat.

Under pressure from the reigning monarch in Dom Luis I, and subsequently his heir Dom Carlos I, the Ramal de Tomar branch line was constructed, connecting Tomar with the main line. Ironically, this ‘by royal decree’ branch line wasn’t competed until 1928 – eighteen years after the dissolution of the monarchy and the establishment of the 1st Republic. The line survives today – the direct service from Lisbon to Tomar is frequent and reliable, and the town is a must-see for lovers of historic and medieval architecture.

Meanwhile, as construction of the Linho do Norte from Lisbon moved apace, engineers began laying the northern section of the line in 1863. Bridging the formidable obstacle of the Douro River was initially set aside – instead, the line ran from Porto’s sister-city Vila Nova da Gaia on the south bank, down to Estarreja where it swept inland to avoid the marshlands surrounding the great lagoon at Aveiro.

Meanwhile, as construction of the Linho do Norte from Lisbon moved apace, engineers began laying the northern section of the line in 1863. Bridging the formidable obstacle of the Douro River was initially set aside – instead, the line ran from Porto’s sister-city Vila Nova da Gaia on the south bank, down to Estarreja where it swept inland to avoid the marshlands surrounding the great lagoon at Aveiro.

The line entered Aveiro itself a year later – famous today for its canals and colourful moliceiro boats, the city and its salinas salt pans have been a major supplier of salt since medieval times. Local industrialists campaigned for the railway, understanding the opportunities train transportation represented and the increased profits which might follow.

The line arrived at the historic city of Coimbra in April 1864. Sitting just north of its centre, the mainline Coimbra ‘B’ station is surprisingly unimpressive, considering Coimbra University is Portugal’s oldest academic institution, and was beloved by both the Avis and Braganza royal dynasties. A short branch line was constructed, running parallel to the Mondego River before terminating at the more-stately Coimbra ‘A’. Sadly, this station was demolished in January 2025, and the short section of line is to be replaced a dedicated electric bus service: the Metro Mondego Metrobus.

The line arrived at the historic city of Coimbra in April 1864. Sitting just north of its centre, the mainline Coimbra ‘B’ station is surprisingly unimpressive, considering Coimbra University is Portugal’s oldest academic institution, and was beloved by both the Avis and Braganza royal dynasties. A short branch line was constructed, running parallel to the Mondego River before terminating at the more-stately Coimbra ‘A’. Sadly, this station was demolished in January 2025, and the short section of line is to be replaced a dedicated electric bus service: the Metro Mondego Metrobus.

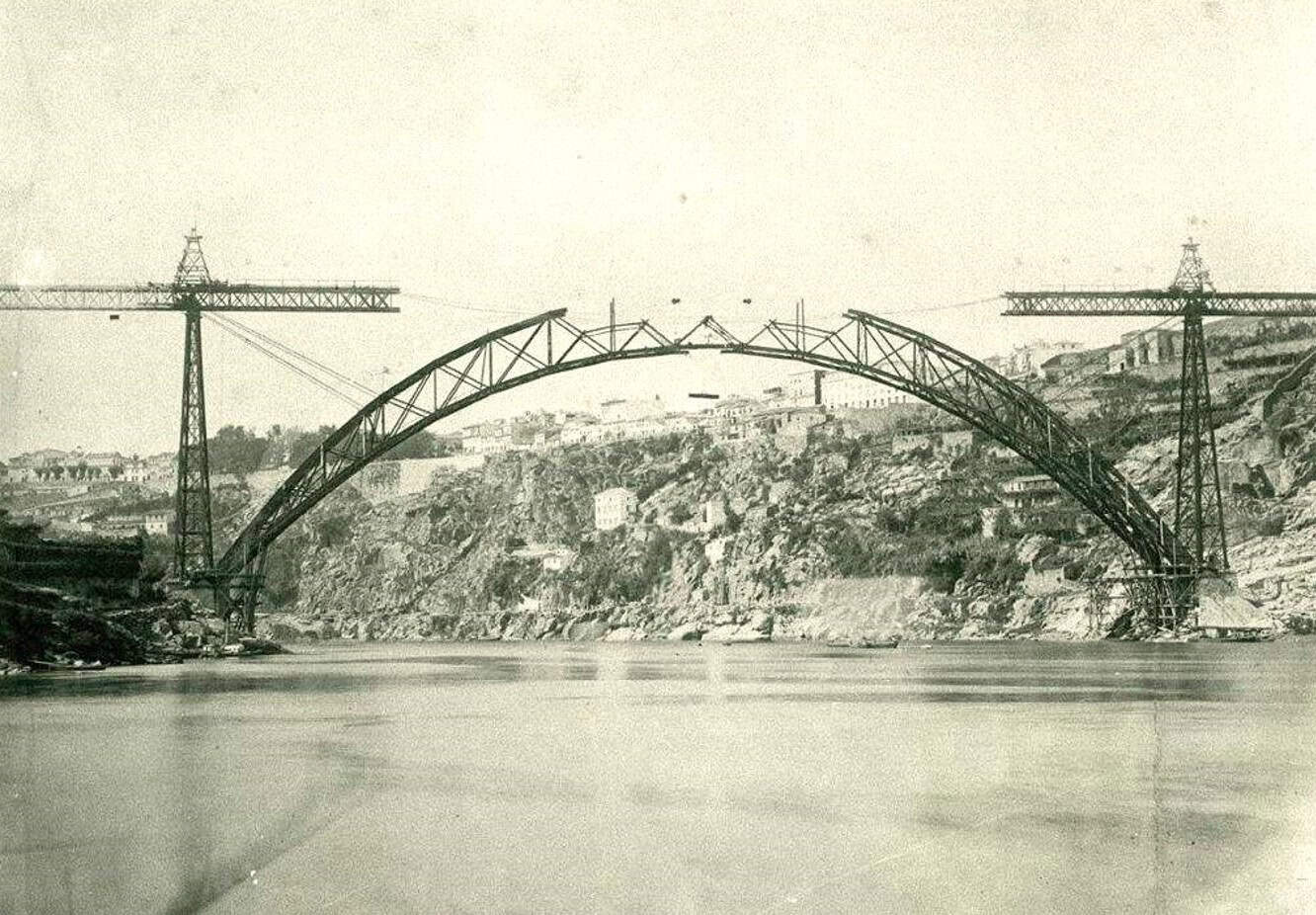

Shortly after the northern line’s arrival into Coimbra, the southern section from Entroncamento to Soure was completed in May 1864. The two lines became one as the final 30km between Soure and Coimbra were completed in July that same year. However, the Linha do Norte wasn’t officially inaugurated until 1878, with the completion of the Ponte de Dona Maria Pia which took the line across the Douro River from Vila Nova da Gaia and into Porto.

Shortly after the northern line’s arrival into Coimbra, the southern section from Entroncamento to Soure was completed in May 1864. The two lines became one as the final 30km between Soure and Coimbra were completed in July that same year. However, the Linha do Norte wasn’t officially inaugurated until 1878, with the completion of the Ponte de Dona Maria Pia which took the line across the Douro River from Vila Nova da Gaia and into Porto.

The bridge was designed by Gustave Eiffel and his team of engineers. Eiffel lived in the small northern village of Barcelinhos for two years and designed a number of bridges in Portugal: crossings over the Rivers Neiva and Caminho, the River Lima at Viana do Castelo, the River Cavado at Barcelos (a short walk from his home), and most-famously the River Douro (in more than one location).

The bridge was designed by Gustave Eiffel and his team of engineers. Eiffel lived in the small northern village of Barcelinhos for two years and designed a number of bridges in Portugal: crossings over the Rivers Neiva and Caminho, the River Lima at Viana do Castelo, the River Cavado at Barcelos (a short walk from his home), and most-famously the River Douro (in more than one location).

Being close to the mouth of the river and the influence of Atlantic tides, the Douro is prone to strong currents as it passes between Porto and Gaia, and the predominantly gravel riverbed ruled out the use of mid-river piers. Eiffel’s solution for the Maria Pia bridge was to construct a wrought-iron, lattice-girder crescent, and upon completion the bridge was the longest single-arched span in the world. It’s often mistaken for the more-famous Ponte de Dom Luis I which was constructed downriver eight years later (in 1886) – Theophile Seyrig, Eiffel’s former business partner and co-designer of the Maria Pia, also designed the Dom Luis.

The Maria Pia was closed in 1991 – being only single track and with speed restrictions of 20km, the bridge was a bottleneck in the railway network and was replaced by the sleek Ponta de Sao Joao. Arguably the best view of the old bridge is from the new: as you’re leaving Porto and heading south, be sure to look right as you cross the river.

The Linho do Norte’s terminus in Porto is the Estacao Ferroviaria de Campanha, or Campanha for short. The station was originally named the Estacao de Caminho de Ferro do Pinheiro, having been built on lands owned by the Quinta do Pinheiro estate. Opened in 1875, Pinheiro-Campanha was the connection between the Linha do Douro and the Linho do Minho – the Minho line travels north from Porto to the cities of Braga, Viana do Castelo, and Valenca on Portugal’s northern border with Spain.

The Linho do Norte’s terminus in Porto is the Estacao Ferroviaria de Campanha, or Campanha for short. The station was originally named the Estacao de Caminho de Ferro do Pinheiro, having been built on lands owned by the Quinta do Pinheiro estate. Opened in 1875, Pinheiro-Campanha was the connection between the Linha do Douro and the Linho do Minho – the Minho line travels north from Porto to the cities of Braga, Viana do Castelo, and Valenca on Portugal’s northern border with Spain.

If you’re thinking of combining Lisbon and Porto, our recommendation is to take the train over driving or flying: 1st class travel is cheap, we’ll prebook your tickets, hotel transfers are included, and it’s your chance to see more of rural and urban Portugal.

If you’re thinking of combining Lisbon and Porto, our recommendation is to take the train over driving or flying: 1st class travel is cheap, we’ll prebook your tickets, hotel transfers are included, and it’s your chance to see more of rural and urban Portugal.

We specialise in personalised holidays to Portugal.

Call our team 017687 721070 to begin planning your own personalised trip.

Follow us online