‘Getting off the beaten track’ is an often overused phrase, but it’s entirely apt if you’re hoping to explore the less-visited towns and cities across Portugal. Sometimes your destination is the goal; occasionally it’s a bonus, as it can be more about the journey itself and the evolving landscapes the carriage windows frame so perfectly. With this in mind, we give you our pick of Portugal’s Best Railway Journeys…

The Linha do Douro is consistently voted one of the top ten train routes in Europe.

The Linha do Douro is consistently voted one of the top ten train routes in Europe.

Departing from one of Porto’s famous architectural landmarks, the Sao Bento train station, the first hour of your journey takes you northwest, through commuter towns such as Ermeside and Penafiel. These gradually fade away, replaced by rustic villages and isolated olive farms. The views are magnificent as the railway snakes its way upriver to Pinhao, overlooked by an iron-beamed Gustave Eiffel-designed bridge. This sleepy hamlet is arguably the true centre of the port industry. Barrels of new wine were once loaded onto Rabelo boats here, for transportation to the port houses in Gaia. The train took over in the early 1900s, but has since been superseded by road tankers.

The latter section of the line, from Pinhao to its current end at Pocinho, is certainly the most-rugged and remote, passing by the Barragem de Valeira Dam and hydroelectric power station, the narrow Cachao da Valeira river gorge, and over the Ponte Ferradosa bridge. The line continues a further 28km beyond Pocinho to the border, but services on the Spanish side were discontinued in 1984. There’s talk of the reinstating 30km of the line from here to Barca d’Alva, and perhaps one day a high-speed link between Lisbon and Madrid.

The latter section of the line, from Pinhao to its current end at Pocinho, is certainly the most-rugged and remote, passing by the Barragem de Valeira Dam and hydroelectric power station, the narrow Cachao da Valeira river gorge, and over the Ponte Ferradosa bridge. The line continues a further 28km beyond Pocinho to the border, but services on the Spanish side were discontinued in 1984. There’s talk of the reinstating 30km of the line from here to Barca d’Alva, and perhaps one day a high-speed link between Lisbon and Madrid.

You could view the Douro Valley line as neglected or forgotten by Comboios de Portugal (the state-owned railway operator). However, the lack of modernisation is one of its many charms. Trains usually have just three or four carriages: the red/white and blue/white carriages are Swiss and Austrian in origin; their windows open fully so give you the best views and opportunities for photographs. There’s usually a silver carriage at the front of the train, just behind the locomotive. They’re our favourites; Portuguese built with a mix of seventies-meets-art-deco.

You could view the Douro Valley line as neglected or forgotten by Comboios de Portugal (the state-owned railway operator). However, the lack of modernisation is one of its many charms. Trains usually have just three or four carriages: the red/white and blue/white carriages are Swiss and Austrian in origin; their windows open fully so give you the best views and opportunities for photographs. There’s usually a silver carriage at the front of the train, just behind the locomotive. They’re our favourites; Portuguese built with a mix of seventies-meets-art-deco.

There’s no buffet car or food/drink service, so I’d recommend stocking up on supplies before you head to the station. I’d also recommend sitting on the right-hand side of the train for the best views, but be ready to close your window as you head into the tunnels to avoid the exhaust fumes from the locomotive. The Class 1400 diesel locomotive at the front of the train was built by English Electric and Vulcan Foundry in the late 1960s, based on the design of the British Rail Class 20. Most of the old diesel fleet has been retired or demoted to freight work as the Portuguese rail network has been electrified – it’s only really here on the Douro line where they’re still used for passenger services.

Day trips on the Linho do Douro are possible from Porto and Vila Nova da Gaia, but to enjoy the whole line at a more leisurely pace, we recommend our Porto and Douro Valley by Train holiday.

The Fertagus Line is an anomalous part of the Portuguese railway network.

The Fertagus Line is an anomalous part of the Portuguese railway network.

Originally known as the Eixo Norte-Sul (North-South Axis), this is the only privately run passenger line in the country, connecting the Areeiro district of the capital Lisbon to the old ship building city of Setubal. It’s primarily a commuter line and not much to write about on paper. However, it does provide a unique perspective on two of the capital’s most-impressive man-made landmarks.

The first is the Aqueduto das Aguas Livres which dominates the skyline over Campolide station. Built in 1744 to bring much-needed fresh water into the city from the parish of Canecas, the aqueduct consist of thirty-five arches spanning a total distance of 941m, feeding water into the underground Reservatório da Mae d’Agua das Amoreiras in the centre of the city. Testament to their over-engineered design and construction, both structures survived the great earthquake of 1755. However, they didn’t survive the construction of the Barbadinhos reservoir which superseded them – both the aqueduct and the Mae d’Agua were decommissioned in 1968.

The Aqueduto das Aguas Livres will live in infamy, thanks to serial killer Diogo Alves. Known as the Aqueduct Murderer, Diogo attacked and robbed seventy passers by in the mid-1800s, throwing them off the 65m high aqueduct in order to disguise his crimes as suicides. Tried and convicted in 1841, Alves was the penultimate criminal to be hanged in Portugal, but his tale took an even more macabre twist. After his death, his head was preserved and donated to Lisbon’s surgical school: perhaps an early example of neuro-criminology, the head still exists in a glass jar of formaldehyde at Lisbon University and can be viewed by appointment.

The Aqueduto das Aguas Livres will live in infamy, thanks to serial killer Diogo Alves. Known as the Aqueduct Murderer, Diogo attacked and robbed seventy passers by in the mid-1800s, throwing them off the 65m high aqueduct in order to disguise his crimes as suicides. Tried and convicted in 1841, Alves was the penultimate criminal to be hanged in Portugal, but his tale took an even more macabre twist. After his death, his head was preserved and donated to Lisbon’s surgical school: perhaps an early example of neuro-criminology, the head still exists in a glass jar of formaldehyde at Lisbon University and can be viewed by appointment.

Without doubt the highlight of this train journey is the crossing of the magnificent Ponte 25 de Abril bridge. This 2.3km suspension bridge was constructed in 1966 and was originally christened the ‘Ponte Salazar’ – named after Prime Minister Antonio Salazar, leader of the ruling fascist Estado Novo regime. This dark period in the nation’s history saw Europe’s great explorers retreat inwards, as the Salazar regime suppressed outside influences and free speech. A group of middle-ranking army officers, (the ‘April Captains’, as they became known), co-ordinated a military coup on 25th April 1974 by transmitting the song ‘Grandola, Vila Morena’ by Jose Afonso – the transmission instigated a series of synchronised takeovers at key institutions across the city. The Lisboetas took to the streets en-masse, and the government relinquished power six hours later. As a lasting symbol of their ‘Carnation Revolution’, the citizens marched across the bridge, forcibly removed Salazar’s plaque and painted ’25 de Abril’ in its place.

Without doubt the highlight of this train journey is the crossing of the magnificent Ponte 25 de Abril bridge. This 2.3km suspension bridge was constructed in 1966 and was originally christened the ‘Ponte Salazar’ – named after Prime Minister Antonio Salazar, leader of the ruling fascist Estado Novo regime. This dark period in the nation’s history saw Europe’s great explorers retreat inwards, as the Salazar regime suppressed outside influences and free speech. A group of middle-ranking army officers, (the ‘April Captains’, as they became known), co-ordinated a military coup on 25th April 1974 by transmitting the song ‘Grandola, Vila Morena’ by Jose Afonso – the transmission instigated a series of synchronised takeovers at key institutions across the city. The Lisboetas took to the streets en-masse, and the government relinquished power six hours later. As a lasting symbol of their ‘Carnation Revolution’, the citizens marched across the bridge, forcibly removed Salazar’s plaque and painted ’25 de Abril’ in its place.

Uniquely for the Portuguese rail network, the Fertagus Line’s electric multiple units are double decker, and sitting on the top deck is a must for the best view as you cross the Tagus River. The river pops up as a natural divide throughout Portuguese history, and it’s quite surprising that the first bridge wasn’t built until 1966. The rail platform came even later – it was added as part of a major refurbishment in 1999.

Uniquely for the Portuguese rail network, the Fertagus Line’s electric multiple units are double decker, and sitting on the top deck is a must for the best view as you cross the Tagus River. The river pops up as a natural divide throughout Portuguese history, and it’s quite surprising that the first bridge wasn’t built until 1966. The rail platform came even later – it was added as part of a major refurbishment in 1999.

A second bridge, the Vasco da Gama road bridge, was constructed in 1998 – this 12km bridge was once Europe’s longest bridge until the opening of the Crimean Bridge in 2018. Future plans are being mooted for an extension of the Lisbon Metro under the river, to connect the city with the beaches of the Costa da Caparica on the southbank, a third bridge from Chelas to Barreiro, and possibly a road tunnel from Alcochete to the site of the new airport.

A second bridge, the Vasco da Gama road bridge, was constructed in 1998 – this 12km bridge was once Europe’s longest bridge until the opening of the Crimean Bridge in 2018. Future plans are being mooted for an extension of the Lisbon Metro under the river, to connect the city with the beaches of the Costa da Caparica on the southbank, a third bridge from Chelas to Barreiro, and possibly a road tunnel from Alcochete to the site of the new airport.

Back on the train, you could alight at Pragal to visit one of Lisbon’s most-photographed landmarks: the Santuario de Cristo Rei catholic monument. Although it’s often compared to the more famous statue in Rio, its design was inspired by a much older monument on the island of Madeira. The Cais do Sodre ferry criss-crosses the river throughout the day (departing every fifteen minutes), and it normally takes around thirty minutes to walk up the hill from the ferry terminal the Santuario. You can take a lift (for 5€ per person) up to the viewing platform on statue’s giant plinth for a 360⁰C view of Lisbon’s endless waterfront, the Serra de Sintra to the east and the green hills of the Serra de Arrabida to the south.

Back on the train, you could alight at Pragal to visit one of Lisbon’s most-photographed landmarks: the Santuario de Cristo Rei catholic monument. Although it’s often compared to the more famous statue in Rio, its design was inspired by a much older monument on the island of Madeira. The Cais do Sodre ferry criss-crosses the river throughout the day (departing every fifteen minutes), and it normally takes around thirty minutes to walk up the hill from the ferry terminal the Santuario. You can take a lift (for 5€ per person) up to the viewing platform on statue’s giant plinth for a 360⁰C view of Lisbon’s endless waterfront, the Serra de Sintra to the east and the green hills of the Serra de Arrabida to the south.

Riding the Fertagus Line to its conclusion will bring you to Setubal. Setubal is popular with the residents of Lisbon for its fresh fish, particularly a dish called choco frito. Like so many great recipes, it’s a dish born out of necessity: cuttle fish was seen as poor man’s squid and local fishermen struggled to sell their catches. The fish would end up being traded for beer and wine with local bar keepers – they’d simmer the fish in saltwater with bay and garlic, before dusting them in cornflower and deep frying them. The resultant choco frito were served back to the fishermen as late-night bar snacks – it’s now a staple of restaurant menus across the town and a fabulous end to the train journey.

Riding the Fertagus Line to its conclusion will bring you to Setubal. Setubal is popular with the residents of Lisbon for its fresh fish, particularly a dish called choco frito. Like so many great recipes, it’s a dish born out of necessity: cuttle fish was seen as poor man’s squid and local fishermen struggled to sell their catches. The fish would end up being traded for beer and wine with local bar keepers – they’d simmer the fish in saltwater with bay and garlic, before dusting them in cornflower and deep frying them. The resultant choco frito were served back to the fishermen as late-night bar snacks – it’s now a staple of restaurant menus across the town and a fabulous end to the train journey.

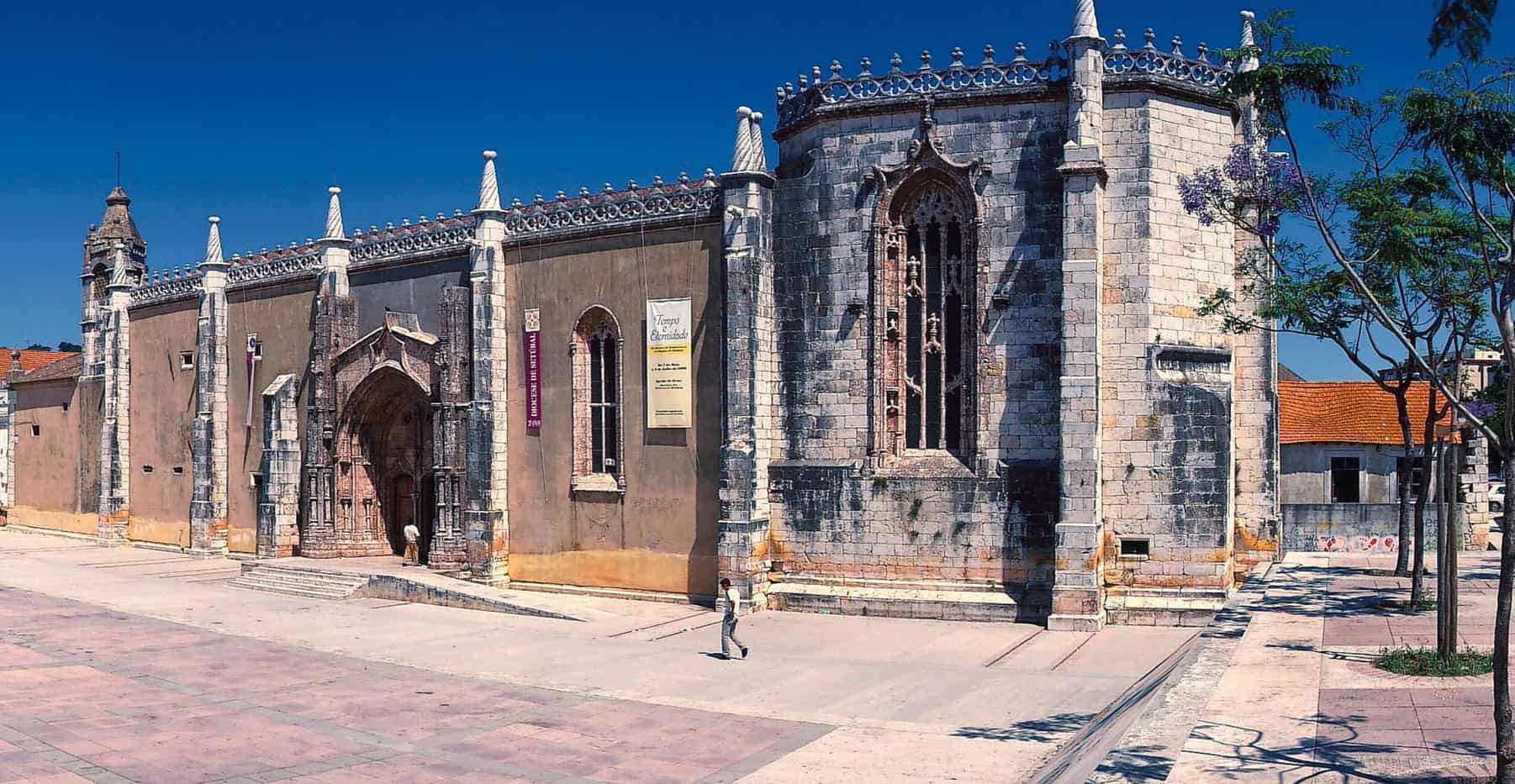

Thanks to its location on the Sado estuary, Setubal was one of Portugal’s largest industrial centres and home to the Lisnave shipyards – it’s been sadly neglected in recent years, but its historic centre around the Convento de Jesus, the Museu de Setubal and the Ingeja do Antigo Mosteiro de Jesus (with its impressive spiralling Solomonic columns) has seen recent renovation.

Being a commuter line, the Fertagus route is best avoided during rush hour, and tickets are purchased from the vending machines on the stations. We’re also toying with the idea of offering day trips to the beautiful medieval city of Evora – the Comboios de Portugal service from Lisbon Oriente to Evora also crosses the Ponte 25 de Avril, and we’ll be including prebooked tickets as part of our day tour.

Being a commuter line, the Fertagus route is best avoided during rush hour, and tickets are purchased from the vending machines on the stations. We’re also toying with the idea of offering day trips to the beautiful medieval city of Evora – the Comboios de Portugal service from Lisbon Oriente to Evora also crosses the Ponte 25 de Avril, and we’ll be including prebooked tickets as part of our day tour.

The Linha de Sintra connects the capital Lisbon with the charming hilltop town of Sintra.

The Linha de Sintra connects the capital Lisbon with the charming hilltop town of Sintra.

The line had quite a sketchy birth: a number of different projects were proposed and cancelled between 1854 and 1887, until the first line was constructed from Alcantara-Terra (just north of the present-day Ponta 25 de Avril) to Sintra. It was quickly extended into the very centre of the in 1889, terminating at the newly constructed Rossio Station. The Estacao de Caminhos de Ferro do Rossio, to give it its full title, was designed by Portuguese architect Jose Luis Monteiro.

Now considered one of Lisbon’s landmark buildings, Monteiro’s intricately detailed front façade, with its ornate horseshoe entrances harked back to the 16th century Manueline architecture more common to the Belem district. Most of the Manueline buildings in the centre of the city were destroyed in the great earthquake of 1755. Montiero’s father was a stone mason, and Jose was trained to work Estremoz marble from an early age – although the budget for the station could only stretch to limestone. The over-extended arches, which form the entrance to the station, are shaped to match the departure and arrival tunnels which take the line west. Look closely above the right-hand door, and you’ll see a bust presenting ‘Father of the Railways’ George Stephenson – and over the left-hand door, Prime Minister Antonio Maria de Fontes Pereira de Melo who was one of the driving forces behind Portuguese railway expansion in the 1800s.

Now considered one of Lisbon’s landmark buildings, Monteiro’s intricately detailed front façade, with its ornate horseshoe entrances harked back to the 16th century Manueline architecture more common to the Belem district. Most of the Manueline buildings in the centre of the city were destroyed in the great earthquake of 1755. Montiero’s father was a stone mason, and Jose was trained to work Estremoz marble from an early age – although the budget for the station could only stretch to limestone. The over-extended arches, which form the entrance to the station, are shaped to match the departure and arrival tunnels which take the line west. Look closely above the right-hand door, and you’ll see a bust presenting ‘Father of the Railways’ George Stephenson – and over the left-hand door, Prime Minister Antonio Maria de Fontes Pereira de Melo who was one of the driving forces behind Portuguese railway expansion in the 1800s.

Entering the station on foot, you’ll find the main concourse is actually the lower level – being spread across seven hills, Lisbon is notoriously undulating, and the platforms and trains are on the upper level, two stores up from street level. To bring the lines into the city, engineers carved two 2.6km tunnels, running from Campolide Station to their high-level terminus here at Rossio. The original wrought iron columns and canopy still provide cover over the platforms. You’ll also see a series of decorative mosaic panels lining the outer walls, celebrating the country’s agricultural history. The panels were commissioned in 1940 as part of the Exposicao do Mundo Portugues: the Portuguese World Exhibition which marked the 800th birthday of the nation. The exhibition was held in the Praca do Imperio, close to the Jeronimos Monastery in Belem, and the panels were relocated to Rossio station when the celebrations ended.

The Linha de Sintra was electrified during the 1950s and the proved to be one of the great success stories of the Portuguese rail network. As the country became better-connected by road and the popularity of the motor car increased, the railways were unfunded and neglected, mothballed, and in many cases, decommissioned. The suburban population to the north and west of Lisbon was growing rapidly, and the Linha de Sintra struggled to keep pace with demand in the late 20th and early 21st century. As a railway journey, the line itself is extremely urban, taking you to the north of Monsanto Park and through the districts of Buraca, Amadora and Massama. Arriving in Sintra can be something of a surprise – just as it’s famous hilltop palace pops into view, the line ducks into an extremely narrow tunnel, before emerging at Sintra station.

A five/ten-minute walk brings you into the pretty centre of the town. Up until the mid-19th century, Sintra was the favoured summer retreat for Portugal’s royal dynasties, as its elevated location provided a cool escape from the heat of central Lisbon. Its centre is dominated by the Palacio Nacional de Sintra – most of the present-day building was constructed by Dom Joao I in the early 1400s, but each subsequent monarch has made his or her mark. Dom Manuel I added the Sala dos Barsoes (the Room of the Coats of Arms) and the palace’s east wing in the late-1400s. The elaborate decoration and intricate detailing is evidence of the wealth which was flowing into Portugal during that time, particularly in the form of gold from its colony in Brazil. The palace’s final occupant was the queen dowager Maria Pia: widow of Dom Luis I and grandmother to Dom Manuel II, the last king of Portugal. Following revolution of 1910 and the establishment of the 1st Republic, the deposed King was exiled to England and lived out his days in Twickenham – Maria Pia left the palace and chose to return to her native Italy, where she died a year later.

A five/ten-minute walk brings you into the pretty centre of the town. Up until the mid-19th century, Sintra was the favoured summer retreat for Portugal’s royal dynasties, as its elevated location provided a cool escape from the heat of central Lisbon. Its centre is dominated by the Palacio Nacional de Sintra – most of the present-day building was constructed by Dom Joao I in the early 1400s, but each subsequent monarch has made his or her mark. Dom Manuel I added the Sala dos Barsoes (the Room of the Coats of Arms) and the palace’s east wing in the late-1400s. The elaborate decoration and intricate detailing is evidence of the wealth which was flowing into Portugal during that time, particularly in the form of gold from its colony in Brazil. The palace’s final occupant was the queen dowager Maria Pia: widow of Dom Luis I and grandmother to Dom Manuel II, the last king of Portugal. Following revolution of 1910 and the establishment of the 1st Republic, the deposed King was exiled to England and lived out his days in Twickenham – Maria Pia left the palace and chose to return to her native Italy, where she died a year later.

Sintra’s most-popular landmark is the colourful Palacio da Pena was commissioned by Queen Dona Maria II at the tail-end of Romanticism in 1854. Inside and out, it’s an eclectic mix of medieval vaulted arches, byzantine domes, Islamic stuccos, and Manueline gothic windows, columns and arcades. The Pena is famously preserved exactly as it was on 4th October 1910, when Dona Maria Amelia, the last queen of Portugal, stayed for her final night before the 1st Republic abolished the monarchy and the royal family fled to Gibraltar. One of our favourite landmarks is the Castelo dos Mouros – the Moorish stronghold dating back to the 9th century, when the region was under Muslim rule. It fell to the Portuguese shortly after Dom Afonso I’s successful siege of Lisbon in 1147 – Gualdim Pias, a prominent figure in medieval Portugal thanks to his association with the Knights Templar, was granted governorship of a fledging Sintra. As the moors retreated south (and eventually across the Mediterranean), the protection offered by the castle became less important, and the settlement outside the fortified walls expanded quickly as new residents were drawn from across the Tejo floodplains. Sintra was officially granted town status in 1154.

Sintra’s most-popular landmark is the colourful Palacio da Pena was commissioned by Queen Dona Maria II at the tail-end of Romanticism in 1854. Inside and out, it’s an eclectic mix of medieval vaulted arches, byzantine domes, Islamic stuccos, and Manueline gothic windows, columns and arcades. The Pena is famously preserved exactly as it was on 4th October 1910, when Dona Maria Amelia, the last queen of Portugal, stayed for her final night before the 1st Republic abolished the monarchy and the royal family fled to Gibraltar. One of our favourite landmarks is the Castelo dos Mouros – the Moorish stronghold dating back to the 9th century, when the region was under Muslim rule. It fell to the Portuguese shortly after Dom Afonso I’s successful siege of Lisbon in 1147 – Gualdim Pias, a prominent figure in medieval Portugal thanks to his association with the Knights Templar, was granted governorship of a fledging Sintra. As the moors retreated south (and eventually across the Mediterranean), the protection offered by the castle became less important, and the settlement outside the fortified walls expanded quickly as new residents were drawn from across the Tejo floodplains. Sintra was officially granted town status in 1154.

Due to the popularity of Sintra with daytrippers, Rossio can be an extremely busy station. Wise visitors take an early train in order to avoid the crowds when visiting the palaces – however, as a consequence you could hit the congestion of the station’s morning rush hour. Travel in the afternoon, and services are busy with tourists heading west to visit the Pena Palace. The direct service departs just after the hour and it takes around forty-minutes to complete the journey – there’s also a service just after half-past, which is slightly slower as it involves a connection at Agualva Cacem.

Due to the popularity of Sintra with daytrippers, Rossio can be an extremely busy station. Wise visitors take an early train in order to avoid the crowds when visiting the palaces – however, as a consequence you could hit the congestion of the station’s morning rush hour. Travel in the afternoon, and services are busy with tourists heading west to visit the Pena Palace. The direct service departs just after the hour and it takes around forty-minutes to complete the journey – there’s also a service just after half-past, which is slightly slower as it involves a connection at Agualva Cacem.

Less well-known (at least to visitors): there’s also a direct service from Lisbon’s Oriente station which takes forty-seven minutes to get to Sintra. It’s much quieter route (after the rush hour), and you can always visit Rossio station on your return journey back into the city. Both services are Urbanos which can’t be prebooked, but if you’d like to take the train during your stay with us in Lisbon, we’ll talk you through the process of purchasing a travel card.

The Linha do Norte is the granddaddy of the Portuguese rail network.

The Linha do Norte is the granddaddy of the Portuguese rail network.

Lisbon and the northern industrial centre of Porto were the first Portuguese cities to be connected by rail. Inaugurated on 28th October 1856, the initial 40km of the Linha do Norte ran from Lisbon to the small town of Carregado – rather than heading directly north, a more easterly route was chosen to take advantage of the naturally-flat terrain of the Estuario do Tejo.

The start point for Portugal’s oldest line is also the country’s oldest railway station: Santa Apolonia. Its stately facade has been a prominent landmark on the Lisbon’s waterfront since 1865 – the station was inexplicably painted sky blue in the 1990s; thankfully, its original, distinctive red colour scheme made a welcome return in 2022, during work to convert the south wing into the Editory Riverside Hotel.

The start point for Portugal’s oldest line is also the country’s oldest railway station: Santa Apolonia. Its stately facade has been a prominent landmark on the Lisbon’s waterfront since 1865 – the station was inexplicably painted sky blue in the 1990s; thankfully, its original, distinctive red colour scheme made a welcome return in 2022, during work to convert the south wing into the Editory Riverside Hotel.

The line reached Santarem by 1861 and Entroncamento a year later. Entroncamento was, and still is, a crucial hub – if you’re travelling around the network today, you’ll often change trains here. It’s the point at which many of the smaller regional lines intersect with the main line; indeed, the word itself, entroncamento, translates into English as junction. It’s a fitting location for the Museu Nacional Ferroviar – the National Railway Museum, which opened its doors in 2007.

The line reached Santarem by 1861 and Entroncamento a year later. Entroncamento was, and still is, a crucial hub – if you’re travelling around the network today, you’ll often change trains here. It’s the point at which many of the smaller regional lines intersect with the main line; indeed, the word itself, entroncamento, translates into English as junction. It’s a fitting location for the Museu Nacional Ferroviar – the National Railway Museum, which opened its doors in 2007.

The museum charts the one-hundred-and-sixty-year history of the railway network, and its evolution and impact on Portuguese society. It also preserves and exhibits historic locomotives, rolling stock and heritage real estate, including Dom Luis’ royal train, a roundhouse turntable from 1911, and the original workshops which once maintained the country’s steam locomotives.

Approaching the end of 1862, the planning and implementation of the line thus far had been marred in controversy. Following their own domestic railway booms, speculating British and French industrialists promised large investments which failed to materialise, leaving the Portuguese state to pick up the bill. In an effort to reduce costs, the contentious decision was made to bypass the historic city of Tomar.

Approaching the end of 1862, the planning and implementation of the line thus far had been marred in controversy. Following their own domestic railway booms, speculating British and French industrialists promised large investments which failed to materialise, leaving the Portuguese state to pick up the bill. In an effort to reduce costs, the contentious decision was made to bypass the historic city of Tomar.

To the modern-day visitor, Tomar is a peaceful rural town with beautifully preserved medieval architecture – however, at the tail end of the 1800s, the Portuguese monarchy were still acutely they owed their existence to Tomar and its founding father, the 12th century crusader named Gauldim Pais.

Pias was the Grand Master of the Portuguese order of the Knights Templar – his crusading nobles fought for Dom Afonso I, helping to install him as ruler of the Kingdom of Portugal in 1143. As thanks, they were granted estates in key strategic locations across the country, including Tomar where they established their main stronghold. Following the Catholic Church’s violent dissolution of the Templars, the crusaders ‘rebranded’ as the Order of Christ. They swore allegiance to the monarch and were key to Portugal’s Age of Discoveries, helping to establish colonies in Africa, India and Brazil. The Portuguese crown accumulated great wealth, and the Order of Christ was seen as the monarch’s right-hand by generations of kings and queens – and by association, the town of Tomar was an important royal seat.

Pias was the Grand Master of the Portuguese order of the Knights Templar – his crusading nobles fought for Dom Afonso I, helping to install him as ruler of the Kingdom of Portugal in 1143. As thanks, they were granted estates in key strategic locations across the country, including Tomar where they established their main stronghold. Following the Catholic Church’s violent dissolution of the Templars, the crusaders ‘rebranded’ as the Order of Christ. They swore allegiance to the monarch and were key to Portugal’s Age of Discoveries, helping to establish colonies in Africa, India and Brazil. The Portuguese crown accumulated great wealth, and the Order of Christ was seen as the monarch’s right-hand by generations of kings and queens – and by association, the town of Tomar was an important royal seat.

Under pressure from the reigning monarch in Dom Luis I, and subsequently his heir Dom Carlos I, the Ramal de Tomar branch line was constructed, connecting Tomar with the main line. Ironically, this ‘by royal decree’ branch line wasn’t competed until 1928 – eighteen years after the dissolution of the monarchy and the establishment of the 1st Republic. The line survives today – the direct service from Lisbon to Tomar is frequent and reliable, and the town is a must-see for lovers of historic and medieval architecture.

Meanwhile, as construction of the Linho do Norte from Lisbon moved apace, engineers began laying the northern section of the line in 1863. Bridging the formidable obstacle of the Douro River was initially set aside – instead, the line ran from Porto’s sister-city Vila Nova da Gaia on the south bank, down to Estarreja where it swept inland to avoid the marshlands surrounding the great lagoon at Aveiro.

Meanwhile, as construction of the Linho do Norte from Lisbon moved apace, engineers began laying the northern section of the line in 1863. Bridging the formidable obstacle of the Douro River was initially set aside – instead, the line ran from Porto’s sister-city Vila Nova da Gaia on the south bank, down to Estarreja where it swept inland to avoid the marshlands surrounding the great lagoon at Aveiro.

The line entered Aveiro itself a year later – famous today for its canals and colourful moliceiro boats, the city and its salinas salt pans have been a major supplier of salt since medieval times. Local industrialists campaigned for the railway, understanding the opportunities train transportation represented and the increased profits which might follow.

The line arrived at the historic city of Coimbra in April 1864. Sitting just north of its centre, the mainline Coimbra ‘B’ station is surprisingly unimpressive, considering Coimbra University is Portugal’s oldest academic institution, and was beloved by both the Avis and Braganza royal dynasties. A short branch line was constructed, running parallel to the Mondego River before terminating at the more-stately Coimbra ‘A’. Sadly, this station was demolished in January 2025, and the short section of line is to be replaced a dedicated electric bus service: the Metro Mondego Metrobus.

The line arrived at the historic city of Coimbra in April 1864. Sitting just north of its centre, the mainline Coimbra ‘B’ station is surprisingly unimpressive, considering Coimbra University is Portugal’s oldest academic institution, and was beloved by both the Avis and Braganza royal dynasties. A short branch line was constructed, running parallel to the Mondego River before terminating at the more-stately Coimbra ‘A’. Sadly, this station was demolished in January 2025, and the short section of line is to be replaced a dedicated electric bus service: the Metro Mondego Metrobus.

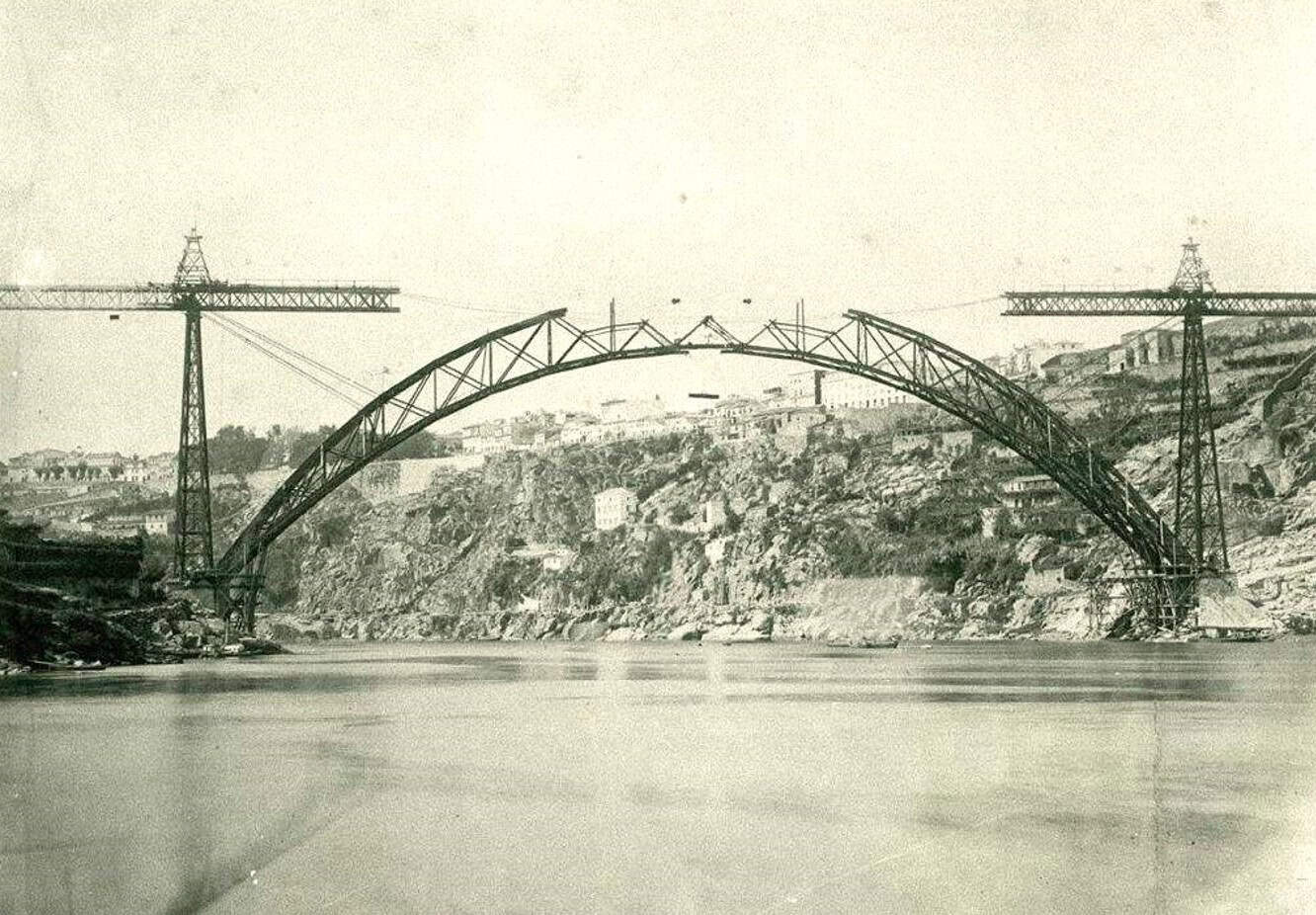

Shortly after the northern line’s arrival into Coimbra, the southern section from Entroncamento to Soure was completed in May 1864. The two lines became one as the final 30km between Soure and Coimbra were completed in July that same year. However, the Linha do Norte wasn’t officially inaugurated until 1878, with the completion of the Ponte de Dona Maria Pia which took the line across the Douro River from Vila Nova da Gaia and into Porto.

Shortly after the northern line’s arrival into Coimbra, the southern section from Entroncamento to Soure was completed in May 1864. The two lines became one as the final 30km between Soure and Coimbra were completed in July that same year. However, the Linha do Norte wasn’t officially inaugurated until 1878, with the completion of the Ponte de Dona Maria Pia which took the line across the Douro River from Vila Nova da Gaia and into Porto.

The bridge was designed by Gustave Eiffel and his team of engineers. Eiffel lived in the small northern village of Barcelinhos for two years and designed a number of bridges in Portugal: crossings over the Rivers Neiva and Caminho, the River Lima at Viana do Castelo, the River Cavado at Barcelos (a short walk from his home), and most-famously the River Douro (in more than one location).

The bridge was designed by Gustave Eiffel and his team of engineers. Eiffel lived in the small northern village of Barcelinhos for two years and designed a number of bridges in Portugal: crossings over the Rivers Neiva and Caminho, the River Lima at Viana do Castelo, the River Cavado at Barcelos (a short walk from his home), and most-famously the River Douro (in more than one location).

Being close to the mouth of the river and the influence of Atlantic tides, the Douro is prone to strong currents as it passes between Porto and Gaia, and the predominantly gravel riverbed ruled out the use of mid-river piers. Eiffel’s solution for the Maria Pia bridge was to construct a wrought-iron, lattice-girder crescent, and upon completion the bridge was the longest single-arched span in the world. It’s often mistaken for the more-famous Ponte de Dom Luis I which was constructed downriver eight years later (in 1886) – Theophile Seyrig, Eiffel’s former business partner and co-designer of the Maria Pia, also designed the Dom Luis.

The Maria Pia was closed in 1991 – being only single track and with speed restrictions of 20km, the bridge was a bottleneck in the railway network and was replaced by the sleek Ponta de Sao Joao. Arguably the best view of the old bridge is from the new: as you’re leaving Porto and heading south, be sure to look right as you cross the river.

The Linho do Norte’s terminus in Porto is the Estacao Ferroviaria de Campanha, or Campanha for short. The station was originally named the Estacao de Caminho de Ferro do Pinheiro, having been built on lands owned by the Quinta do Pinheiro estate. Opened in 1875, Pinheiro-Campanha was the connection between the Linha do Douro and the Linho do Minho – the Minho line travels north from Porto to the cities of Braga, Viana do Castelo, and Valenca on Portugal’s northern border with Spain.

The Linho do Norte’s terminus in Porto is the Estacao Ferroviaria de Campanha, or Campanha for short. The station was originally named the Estacao de Caminho de Ferro do Pinheiro, having been built on lands owned by the Quinta do Pinheiro estate. Opened in 1875, Pinheiro-Campanha was the connection between the Linha do Douro and the Linho do Minho – the Minho line travels north from Porto to the cities of Braga, Viana do Castelo, and Valenca on Portugal’s northern border with Spain.

The completion of the Ponte de Dona Maria Pia in 1886 finally brought the Linho do Norte into Porto, and the moment was marked by a special Royal Inter Cidades service from Lisbon.

The completion of the Ponte de Dona Maria Pia in 1886 finally brought the Linho do Norte into Porto, and the moment was marked by a special Royal Inter Cidades service from Lisbon.

By the start of the 20th century, a more central station was required for the Third Order commuter lines which would connect central Porto to its suburbs, and to the First Order mainline to Lisbon. The Estacao Ferroviaria de Sao Bento was proposed – to be built on the site of the derelict Sao Bento da Ave Maria convent in the district of Cedofeita.

The tricky engineering of the 700m long Dom Carlos I tunnel was tackled first, to bring the line from Alameda das Fontainhas (close to the Maria Pia Bridge), directly into today’s station on the Praca de Almeida Garrett. A tunnel collapse delayed the project in 1897 – a falling out between architect Jose Marques da Silva and the city authorities delayed the completion of the station further.

The tricky engineering of the 700m long Dom Carlos I tunnel was tackled first, to bring the line from Alameda das Fontainhas (close to the Maria Pia Bridge), directly into today’s station on the Praca de Almeida Garrett. A tunnel collapse delayed the project in 1897 – a falling out between architect Jose Marques da Silva and the city authorities delayed the completion of the station further.

Sao Bento Station finally opened its doors to the public in 1916, and its impressive entrance hall is decorated with approximately 20,000 blue and white azulejo tiles. Azulejos have been an important element of Portuguese architecture for eight-hundred years – these beautifully painted, glazed ceramic tiles have their roots in the Islamic architecture of the Moorish occupation of Iberia. Indeed, the word azulejo is derived from the Arabic ‘zellij’ meaning polished stone, and the artform was adopted by the early architects of the Kingdom of Portugal – initially as decoration for religious buildings and royal palaces, before becoming the more widely used.

Sao Bento Station finally opened its doors to the public in 1916, and its impressive entrance hall is decorated with approximately 20,000 blue and white azulejo tiles. Azulejos have been an important element of Portuguese architecture for eight-hundred years – these beautifully painted, glazed ceramic tiles have their roots in the Islamic architecture of the Moorish occupation of Iberia. Indeed, the word azulejo is derived from the Arabic ‘zellij’ meaning polished stone, and the artform was adopted by the early architects of the Kingdom of Portugal – initially as decoration for religious buildings and royal palaces, before becoming the more widely used.

The mosaic on the south wall depicts the arrival of Philippa of Lancaster, (sister of Henry IV), into Porto. Philippa married Dom Joao I in Porto on 14th February 1387, becoming Queen Consort of Portugal and sealing an Anglo-Portuguese Alliance known as the Treaty of Windsor: the oldest, still-active union between two nations.

The mosaic on the south wall depicts the arrival of Philippa of Lancaster, (sister of Henry IV), into Porto. Philippa married Dom Joao I in Porto on 14th February 1387, becoming Queen Consort of Portugal and sealing an Anglo-Portuguese Alliance known as the Treaty of Windsor: the oldest, still-active union between two nations.

Their fourth son, the Infante Dom Henrique, perhaps better known as Henry the Navigator, appears below – his invasion of Ceuta in 1415 kick-started Portugal’s Age of Discoveries, their mapping of the sea route from Europe to India, and their colonization of Brazil.

The Battle of Valdevez is commemorated on the northern wall – a conflict fought in the 12th century between Alfonso VII of Leon and Afonso I of Portugal. Victory for Afonso I resulted in the Treaty of Zamora, and established Portugal as a free Kingdom.

The Battle of Valdevez is commemorated on the northern wall – a conflict fought in the 12th century between Alfonso VII of Leon and Afonso I of Portugal. Victory for Afonso I resulted in the Treaty of Zamora, and established Portugal as a free Kingdom.

A rendering Luis Camoes’ legend of Egas Moniz appears below. Moniz was a knight and tutor to Dom Afonso I in his youth – when the adult Afonso reneged on an oath of allegiance to Alfonso VII, Moniz offer his life and that of his family as penance. Moved by his chivalry, Alfonos spare the family and ended his ongoing siege of Guimaraes (the family’s home city).

Surrounding these historical representations, you’ll see stylised depictions of rural Portuguese life – some are in blue and white, others in full colour. It took artist Jorge Colaco eleven years to complete the concourse project and the station is now designated a National Monument of Portugal.

If you’re thinking of combining Lisbon and Porto, our recommendation is to take the train over driving or flying: 1st class travel is cheap, we’ll prebook your tickets, hotel transfers are included, and it’s your chance to see more of rural and urban Portugal.

If you’re thinking of combining Lisbon and Porto, our recommendation is to take the train over driving or flying: 1st class travel is cheap, we’ll prebook your tickets, hotel transfers are included, and it’s your chance to see more of rural and urban Portugal.

We specialise in personalised holidays to Portugal.

Call our team 017687 721070 to begin planning your own personalised trip.

Follow us online